Begin with the small

| Vandana Shiva gave the first in a series of lectures, Imagining a Cultural Commons, organised by the London International Festival of Theatre in May 2003. The Indian environmental activist, quantum physicist and author talks with Wallace Heim about the importance of the arts for biological and cultural diversity.

|

|

Wallace |

You have said that the arts and theatre are important to you, although your work is more directed towards activism and education. I’d like to start with your own experience of rituals and celebrations in India and what these have meant to you.

|

|

Vandana |

Vandana Shiva, photo courtesy LIFT |

One of those festivals is Akti, which is done at the beginning of the annual cultivation season. It’s theatre in real life. In 1991, I was travelling the country trying to inform farmers, peasant groups, and tribal groups about this new emerging trade treaty, at that time it was still the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs, which was a new set of international laws that were going to force the patenting of life, including seed.

When I was in a tribal area in central India, one of the tribals mentioned casually that seed can’t ever be privately owned, it belongs to a whole community and they reaffirm that every year with Akti. So I asked when is the next festival and it was a few months down the line, so I said "I’m going to come." I visited about twenty villages which were performing this beautiful ritual, very beautiful ritual. Every family brings their rice to the local divinity in folded leaves called donas. Each dona is different, and they are all put together and mixed and exchanged. The mixing is both the sharing and also a reminder that isolated rice which is not being exchanged will have disease. It will be prone to pest attacks, it will lose resilience.

The ritual embodies three things in one go. The reaffirmation of biodiversity being a common legacy. It’s a reaffirmation of the dependence we have on larger forces on this planet, because it’s an invocation asking for the rain and nature and the cycles of the weather to co-operate, so that the harvest will be enough to look after the needs of the community. And it’s a reaffirmation of ecological balance. And that’s just one ritual.

The most vibrant rituals are practised in areas that haven’t fallen victim to industrial agriculture - which is the end to ritual. We have a harvest festival in January in southern India. One day is for crops and one day is for animals, and on that day the cattle are decorated in the most beautiful ways. Indian cattle don’t have their horns removed because they are free-range cattle and their horns are not dangerous weapons. And they’re let loose. That day they do no work and no one is supposed to tell them where to go and what to do and so they are just going all over the place.

The interesting thing is that the people don’t do this ritual with the cross-bred cattle. Indian breeds of cattle were what we call ‘dual purpose’, the males gave the energy, the females gave the milk and both gave soil fertility. But at a certain point, the only purpose of a cow became milk production. Animal energy had no role because you were supposed to depend on fossil fuels. Cross-bred breeds were designed, bringing in Jersey Holsteins, just to maximise milk production. And there is no purpose then for the male calf. They are slaughtered. But the interesting thing is, no one’s telling society, no one’s telling culture about all this and yet there is a way in which, in the art of the society, in the rituals of the society, in the celebration of the sacred in society, festivals that celebrate the sanctity of seed – don’t do it with hybrids which don’t renew. They don’t do it with cross-bred cattle which don’t have a self-propagating, self-rejuvenating tendency. And it’s a social decision that’s just been made informally. And it has been very touching for me to notice it.

|

|

Wallace |

That’s chilling. Here, so many of those renewing seasonal rituals have gone. Farming is industrialised through and through. It’s often a case of having to, trying to reinvent that connection again, sometimes, by adapting rituals from other cultures. Which brings me on to the next question. There is criticism now about practitioners using rituals and contemporary work from other cultures in an appropriating way. And there is a larger question as to how, across cultures, artists and theatre practitioners can work together equitably and fairly, especially as so many environmental issues recognise no political boundaries

|

|

Vandana |

a traditional welcome

photo courtesy vandanashiva.org |

All cultural evolution has taken place through fertilising of ideas, through cultural forms and imaginative metaphors being taken from across cultures and given a whole new dimension, given a new life. It’s a bit like that seed in Akti. If left to itself one farmer’s seed planted every year will eventually degrade. But it’s renewal comes out of exchange, it’s renewal comes out of being planted on another field, being looked after by another hand.

I don’t think it’s the exchange or the borrowings that really make for exploitation. I think it’s other things in the framework of relationships between cultures that makes for exploitation. We do have a colonial legacy, and we now have globalisation and market-driven contexts in which those who have power can appropriate from those who do not. Those who are in the market can appropriate from those who are in the commons. And that is the problem. For example, one of the big issues I worked on was Neem. It’s a longish story and it has to do with creativity and arts, too. We have a beautiful tree in India called the Neem. And the Neem has been used by my mother and my grandmother to protect grain. It’s been our pest control agent and it’s planted in every back yard. In south India it is planted in the village centre and is worshipped along with the Bodhi tree. In 1984, we started a mobilisation which was both a legal challenge to patenting the Neem, and a celebration of planting the Neem. There were huge fairs where we would celebrate the thousand uses of the Neem tree. This whole appropriation for private monopoly had to be struggled against. We had to reclaim the Neem, and set the Neem free. I then went to Africa and every part of Africa is planted with Neem. Africa didn’t patent it nor did India charge them royalties. So exchange isn’t the problem. The terms of exchange are the problem. Trade isn’t the problem, the terms of trade are the problem. And so we have to sort out the terms rather than try and be insular.

I think fertilising each other’s ideas is just wonderful. It’s amazing. We’ve all enriched ourselves through that. The point is one shouldn’t try and seek private benefit, cultural power, cultural domination out of that exchange and that needs sensitivity, it needs respect, it needs mutual giving and taking and knowing that you are receiving a gift and you have to carry it through with all the integrity and all the care that it deserves.

|

|

Wallace |

The challenges of speaking across cultures also happen within a society. Many people now are working within corporations and within government or institutional settings, using theatre and the arts to facilitate a change in business and corporate practices in relation with the environment. In your work, what ways have you found of speaking across these divides?

|

|

Vandana |

I think different individuals and different corporations have extremely different behaviour patterns and cultures. There can be extremely large corporations which are still able to respect critical assessment and listen to it with openness. There are others who are so closed that any honest appraisal creates a very, very vicious lashing out. If a corporation wants to make money at any cost it will not re-evaluate what it’s doing no matter what, even if it is costing the earth. But if a corporation thinks yes, it should make profits but it shouldn’t unleash ecological destruction, cultural dislocation and displacement, then it will be constantly on the alert to get signals telling it where it is going wrong.

I think the arts are a very, very important avenue for transformation because we’re in this strange situation where if you really look at what the World Trade Organisation has meant, it has basically meant there is only one kind of citizen in the world, which is the global corporation, and ordinary citizens and ordinary people are second class citizens. I don’t think there was a thinking that went behind that structure. I think it was just for the convenience of finding quick markets and the maximisation of the movement of capital.

But the implications of that thinking are cosmological. Its implications are for human rights and how we think of what is a human being, what is a human being for. Now, there are three levels at which you can start addressing this problem – the problem that the human has been displaced by the non-human, the organisation and corporations have been given a higher status and given all the rights of a human being and no responsibilities of a human being. Firstly, you can do it in the old style politics which doesn’t have a richness, it doesn’t have a texture. It reinforces existing, assumed categories. Secondly, one does need to address the problem in a very accurate form through the work of science, through the actual counting of figures – in India for example that is counting the number of farmer suicides or how many rupees did an Indian peasant lose in growing potatoes for export. But that counting is far more directed to not having that pain of the powerless written off, because unfortunately it is the case that the pain of the powerless is disregarded unless it’s turned into communication of the dominant system which is figures and graphs.

But, and this is the third level, I still feel that with human transformation, the power to reach deep within to make change, it is really the arts and culture which carry that power. And therefore even though I am not an artist and I’m not from theatre, I have a very, very deep respect for what can be done.

I know that with ten books I write, those books are not equal, I am not equal, to the two lines a village poet will create on these issues.

|

|

Wallace |

This brings us to democracy. In the European culture, theatre and representative democracy evolved around the same time. Now, there are artists and theatre practitioners trying to reinvent democracy in very small ways and doing this through creating social spaces. Not in a big, national theatre way, but in small events, and in creating public spaces for conversation. I think this work has value not only in what it is telling us about what mainstream theatre isn’t doing now, but it’s also saying what representational democracy isn’t doing right now - which is allowing for those spaces of local, public consensus. Artists, in some ways, are perceiving that need.

|

|

Vandana |

Bija, farmer and seedsaver at Bija Vidyapeeth farm

photo courtesy vandanashiva.org |

I think that democracy is being reinvented in small places and it is in the nature of growth and in the nature of birth and in the nature of regeneration, to begin with the small. The chestnut tree didn’t come as that tree, it came as that little chestnut seed. And you were once an embryo as was I, and as are our future generations. There is sometimes panic when something is not ready-made in it’s full unfolding of a potential. That’s where my own scientific work in quantum theory is constantly helping me to remember that the smallness is not a smallness forever, but smallness embodies an unfolding into largeness.

We are in a time of the silencing of formal democracy, and we can see this in the way that opposition to the war in Iraq is seen as supporting the terrorists – the international debate has been reduced to that. The informal democracy people are trying to create is in the peace movements which are against both the violence of the terrorists and the violence of military aggression. But there are attempts to criminalise protest and to equate people who call for peace with supporters of terrorist action. The only thing that is available in such periods is to begin with the small, that little corner which nobody notices, which won’t be stamped out, and to create the space for democracy, through those tiny imaginations of democracy, in a period of the death of democracy. I think there are two things that artists are very fully aware of, as are scientists and quantum scientists, which is of the complexity and the uncertainty of the world. It was only for a hundred years that we thought that everything was immutable, everything came as essentially determined for ever. It was fixed, it was locked in, nothing could be made to change. During that time, the world was about dealing with amazingly fixed qualities and quantities. It projected that fixed-ness onto human beings, saying that human beings are designed to be violent, they’re designed to be competitive, they’re designed to hurt each other therefore we must have an all powerful state to control them - without ever thinking that the potential for co-operation as much as the potential for competition is shaped by the context into which human beings are put. Co-operation and competition are the result of social interaction and not our essential nature.

It’s potential that matters and potential is in the small. So I really feel that these small spaces where democracy is being reinvented – whether it be through arts and theatre or it be through other alternatives, for example in agriculture – have huge implications because they will unfold into the future. They are shaping history, and already in them are carried the germs of another historical trajectory.

|

|

Wallace |

Practitioners can work in either an urban or a rural sphere, and deal with issues of the local and the global. A seed, GMO’s – these are immediate and intimate points of connection between, say, my body, my food and globalisation.

|

|

Vandana |

Spinning wheel ceremony

photo courtesy vandanashiva.org |

I’ve always been a little puzzled by the thinking that allows it to be imagined that the local and the global are separated planes. The local and the global are interactive and the point is which end you begin with and what you privilege. When you privilege the local, the global becomes a system of mutually interacting, mutually respectful autonomous systems – whether that is for food or for culture for the way we govern ourselves. Or, you can privilege the global in which case the global is in every local, but the local is reshaped on the terms of global privilege. And that’s where genetically modified seed comes in, that’s where global corporations reach the remotest village in India. Subsistence peasants shape their actions on the basis of mythic beliefs. Corporations are using those mythic beliefs as marketing tools – using all our gods and divinities, Gurunanak in Punjab and Hanuman in south India - to be salesmen for Monsanto. They are transporting subsistence peasants down a track from which they cannot retreat.

That’s why we are getting a new phenomena of farm suicides in India. And the farm suicides have in my view become the tragic phase of globalisation at the local level, at the deeply local level.

So there is no separation. The point is what do you privilege, how do you see the interaction, and again, if you come back to that issue of terms of relationship, there is no separation. The point is - what is the relationship. Will the global extinguish the local in its self-expression and turn it into just zones of colonisation? Or will the global be a formation of the free self-expression of the many locals and create a global linked through humility? We have to leave a space for other species on the planet, other cultures, other regions, other countries, and live in the right way with awareness of what is the space that others are entitled to.

|

|

Wallace |

That ties in with the collective statement from The People’s Earth Summit at Johannesburg: “We reaffirm that ‘another world is possible’ and we shall make it happen.” Theatre practitioners and artists are saying that all the time. Are you hopeful that this is happening, that this is possible?

|

|

Vandana |

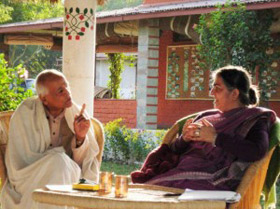

Satish Kumar and Vandana Shiva

photo courtesy vandanashiva.org |

Yes, I’m very hopeful. Again coming back to that issue of small spaces. One of the interviewers that I spoke to yesterday, said “Oh, but the big protests are making a difference.” I said “You’re looking in the wrong place.” The protests aren’t supposed to shape the alternative. The alternative begins where people live, where they teach, where they eat. So if you really want to see whether change is being made look at how it begins in the small places, look now at how organic farming is increasing now on a large scale.

I think if you look at the wrong place for the wrong thing then you’re not going to find that thing. I’m hopeful for the places where people can make changes, not where states or corporations can make changes, but where people can make changes. And their change will influence governments and corporations.

The point is where does the change begin and I believe the change has begun and it’s unfolding. And it carries the future, because that other trajectory, of false advertising and selling to farmers hybrid seeds and pesticides with no idea of the consequences, selling false illusions, is a trajectory of self-destruction. This is the way corporations are dealing with the planet. I’ve called it the suicidal tendency, and it is extinguishing the future.

|

|

Wallace |

I was very struck in your LIFT lecture when you said it’s telling the truth that works – that is what works. That the arts tell a truth but it’s different from a scientific truth. And I’m returning to the first question in a way. There is an experience of a truth that art can bring or ritual can bring or performance or celebration can bring, but it may not have that absolute direct scientific verifiable aspect to it. And I just wondered if you’d been moved by the other truths that you’ve heard people speaking?

|

|

Vandana |

I have been deeply moved by truths that are not verifiable in the scientific way but they are verifiable by human experience. When a play or a painting or a piece of music makes a difference it’s because it is, in a way, being verified through the experience that it triggers in others. That experience is then, in some way, reflecting lived experience or the puzzle of not being able to make sense of things. The arts can do that, the arts can explain confusion, lend clarity to it, in deceitful times in which ‘public relations’ are trying to shape our thinking and our imagination.

I think arts can reveal, arts can tell the truth in a much richer way than science. It is the nature of science to tell the truth a bit at a time. I can tell the truth about farmer suicides in India. When the first five happened, they said “Oh, they were all alcoholics.” And then ten happened, and it was “Oh, they were all alcoholics plus adulterers.” Then 20,000 happened, and then surely it was about debt and seeds and chemicals. The lie was exposed - that this was to do with a personal problem rather than the larger context which is compelling a tragic response. But whatever it is, through the science, you tell one story at a time. The wonderful thing with art is you can tell many stories at a time. Life is many stories at one time and therefore the truth is richer in the communication and the telling of it in the arts.

|

|

Wallace |

In some ways artists and theatre practitioners need to take risks in communicating the big issues, or in developing a language for expressing the experiences of these issues - the patenting of life, intellectual property, genetic modification of seed, climate change and global responsibility. For the mainstream, and much of what is called political theatre here, these issues seem to be outside the areas of interest for some reason and we want to encourage people to take risks and address them

|

|

Vandana |

Vandana Shiva and Adivasi seedkeepers in Jharkhand

photo courtesy vandanashiva.org |

I’ve always given so much weight to carving out the small spaces and letting them grow, including in our work, the seed saving. We started with three seed banks now we’ve established more than twenty-four. You begin with the small, you begin with the do-able, you begin with that which you can do and that which you can do under the most repressive context. And in the doing of it, you make the repression retreat, you change the terms.

It’s very interesting, last year Time Magazine identified ten people who are shaping the future in different fields, and they identified me and Navdanya - our movement for conserving biodiversity. And there was a line at the end - and this was Time Magazine, totally conservative, you know, they’re not the kind of people who would normally touch us with a barge pole – but the last line was ‘and through the work of Navdanya the terms have changed, instead of traditional seeds and agriculture being judged by the yardstick of biotech, the biotech industry is now to be judged by the yardstick of ecological agriculture.’

But to make that yardstick real you’ve to make it happen. To make it happen takes personal commitment. It has to begin with the person, it has to begin at the local. Nurturance for an idea comes from two sources. It comes from partnerships which can make an idea happen, sometimes with small amounts of money which can make an idea grow and find nourishment from other sources. The second thing it really needs is a deep, deep belief that it is possible, that another way is possible. And, because what you bring to life - whether you do it as an artist or you do it as conservationist – is the total function of how much you believe it can be done.

|

published in 2003

2013:

www.vandanashiva.org

www.navdanya.org

Dr. Vandana Shiva is the founder of Navdanya, an organisation to support local farmers in India, to rescue and conserve crops and plants that are being pushed to extinction. Navdanya is a network of seed keepers and organic producers spread across 17 states in India. Navdanya has helped set up 111 community seed banks across the country, trained over 500,000 farmers in seed sovereignty, food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture over the past two decades, and helped setup the largest direct marketing, fair trade organic network in the country. Navdanya has also set up a learning center, Bija Vidyapeeth (School of the Seed / Earth University) on its biodiversity conservation and organic farm in Doon Valley, Uttarakhand, North India. Books by Vandana Shiva include:

Making Peace With The Earth (2013) Pluto Press.

Soil Not Oil (2008) South End Press.

Democratizing Biology: Reinventing Biology from a Feminist, Ecological and Third World Perspective (2007) Paradigm Publishers

Earth Democracy; Justice, Sustainability, and Peace (2005) South End Press.

India on Fire: The Lethal Mix of Free Trade, Famine and Fundamentalism in India (2003) Seven Stories Press.

Water Wars: Pollution, Profits and Privatization (2002) Pluto Press.

Protect or Plunder? Understanding Intellectual Property Rights (2001) Global Issues Series, Zed Books.

Stolen Harvest: The Highjacking of the Global Food Supply (2001) Zed Books.

Tomorrow’s Biodiversity (Prospects for Tomorrow) (2000) Thames and Hudson.

Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge (1998) Green Books.

Monocultures of the Mind: Perspectives on Biodiversity and Biotechnology (1993) Zed Books.

Ecofeminism [with Maria Mies] (1993) Zed Books.

Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development (1989) Zed Books.

|

"These small spaces where democracy is being reinvented – whether it be through arts and theatre or it be through other alternatives, for example in agriculture – have huge implications." :: "I still feel that with human transformation, the power to reach deep within to make change, it is really the arts and culture which carry that power. And therefore even though I am not an artist and I’m not from theatre, I have a very, very deep respect for what the arts can do." :: "Exchange isn’t the problem. The terms of exchange are the problem. Trade isn’t the problem, the terms of trade are the problem. And so we have to sort out the terms rather than try and be insular.

I think fertilising each other’s ideas is just wonderful. We’ve all enriched ourselves through that. The point is one shouldn’t try and seek private benefit, cultural power, cultural domination out of that exchange and that needs sensitivity, it needs respect, it needs mutual giving and taking and knowing that you are receiving a gift and you have to carry it through with all the integrity and all the care that it deserves." :: "With human transformation, the power to reach deep within to make change, it is really the arts and culture which carry that power. And therefore even though I am not an artist and I’m not from theatre, I have a very, very deep respect for what can be done.

I know that with ten books I write, those books are not equal, I am not equal, to the two lines a village poet will create on these issues." :: "It is in the nature of growth and in the nature of birth and in the nature of regeneration, to begin with the small. The chestnut tree didn’t come as that tree, it came as that little chestnut seed. And you were once an embryo as was I, and as are our future generations. There is sometimes panic when something is not ready-made in it’s full unfolding of a potential. That’s where my own scientific work in quantum theory is constantly helping me to remember that the smallness is not a smallness forever, but smallness embodies an unfolding into largeness." :: "One of the interviewers that I spoke to yesterday, said “The big protests are making a difference.” I said “You’re looking in the wrong place.” The protests aren’t supposed to shape the alternative. The alternative begins where people live, where they teach, where they eat. So if you really want to see whether change is being made look at how it begins in the small places.

I think if you look at the wrong place for the wrong thing then you’re not going to find that thing. I’m hopeful for the places where people can make changes, not where states or corporations can make changes, but where people can make changes. And their change will influence governments and corporations." :: "I have been deeply moved by truths that are not verifiable in the scientific way but they are verifiable by human experience. When a play or a painting or a piece of music makes a difference it’s because it is, in a way, being verified through the experience that it triggers in others. That experience is then, in some way, reflecting lived experience or the puzzle of not being able to make sense of things. The arts can do that, the arts can explain confusion, lend clarity to it, in deceitful times in which ‘public relations’ are trying to shape our thinking and our imagination." :: To make something happen takes personal commitment. It has to begin with the person, it has to begin at the local. Nurturance for an idea comes from two sources. It comes from partnerships which can make an idea happen, sometimes with small amounts of money which can make an idea grow and find nourishment from other sources. The second thing it really needs is a deep, deep belief that it is possible, that another way is possible. And, because what you bring to life - whether you do it as an artist or you do it as conservationist – is the total function of how much you believe it can be done."

|