|

Playwrights revisited:

If Brecht were alive today, would he write about global warming? Wallace Heim on Brecht the environmentalist.

In our climate change debate, the environmental journalist Caspar Henderson suggests he would. Environmental issues are arguably the most pressing of any facing humankind, but as yet, there is not a developing field of major contemporary environmental plays. Do we need Brecht? Do we need a Brecht?

One way to consider these questions is to ask what Brechtian theatre has to offer theatre-makers working with environmental themes. Another way is to take a longer view, seeing something more radical suggested by Brecht that may inspire an environmental re-invention of theatre.

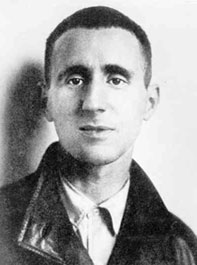

Bertolt Brecht 1898-1956

|

In Brecht’s own writings about theatre, his forcefulness and direction was towards changing human society, towards educating an audience and providing entertainment. Science was a source of fascination, as seen in his play Life of Galileo. For Brecht, the sciences held a potentially liberating power for humankind if their methods and rationality could be applied to human affairs. As to nature, the sciences made the alteration and exploitation of nature possible in order to make the planet a ‘fit’ home for ‘mankind.’ Nature was a resource for scientific and technological experimentation, a treasure to be exploited which, in a Marxist society, would benefit all of humankind, not just those social classes which controlled nature and industrial production. Even Brecht’s theoretical work, A Short Organum for the Theatre is named after Francis Bacon’s Short Organum in which he advocates ‘wringing from Nature her secrets…to make practical use of them.’

So it seems that Brecht’s views of nature are at odds with environmentalist views. But, as Brecht’s theatrical methods have permeated political theatre in the second half of the twentieth century, could these be adaptable tools for making works which propose to change an audience’s perceptions about nature, to change their habits and assumptions about the environment?

Most theatre endeavours to make the familiar strange. Brecht did this differently. His estrangement-effect appealed to reason, intending to produce a critical attitude in the spectator, distanced from any feeling of empathy with the characters of the play, in order that one could see the real motives and forces behind what was thought to be socially unquestioned. Brecht attempted to exclude emotion in favour of reason and ‘objective facts.’ Epic theatre was supposed to force the spectator to consider other possibilities than those expressed in the theatre of the day, and to expose the contradictions and power struggles hidden in bourgeois society. Brecht brought together the events and actions of the everyday with the current political theories and movements of the time.

Some of Brecht’s methods might be made appropriate for environmental works, in the same way that a writer and director may borrow from other genres, traditions and conventions, like the thriller, the docu-drama, or narrative realism. The hazard now, though, is that stripped away from Brecht’s immediate passions, they become tools for didactic theatre, showing a view of nature based mostly on information, politics and science. This theatre can miss out what makes questions about nature so vital, nuanced and imploring. Brecht had Marxism as a theoretical basis, and confined his works to human social relations. Human relations with nature do not have a single theoretical basis, and the experiences, emotions and perceptions involved are different and differently complex than those Brecht explored. And environmentalism now is re-configuring politics, global power and private feelings.

But Brecht offers us an extraordinary example for how to take theatre and performance into new and necessary realms. Brecht could not express what he wanted to express in the theatre of his day. So Brecht changed theatre.

To express what must be expressed about human relations with nature could mean re-inventing theatre, and that could change both how theatre is made in the 21st century and how people respond to the environment in their everyday lives. That change will emerge with the writers, directors, actors and artists and their visions and developing practices. Brecht didn’t work alone, and it may be now in collaborative working that new forms emerge. A changed theatre may take place in small ways; it may show itself firstly in the mainstream; it may take many shapes, not just that developed by one director. But theatre can, and is always, changing in response to what needs to be communicated.

So yes, as Brecht changed theatre to express what needed to be expressed, if he was alive today, he might be making environmental performances, because the environment calls up the most pressing issues and because, it seems, theatre is not responding – yet. But the theatre re-invented may not be Brecht’s.

Brecht left the door open for future change, writing in the Short Organum: ‘There are many conceivable ways of telling a story, some of them known and some still to be discovered.’ © Wallace Heim

published in 2005

|

Brecht could not express what he wanted to express in the theatre of his day. So Brecht changed theatre. To express what must be expressed about human relations with nature could mean re-inventing theatre in the 21st century. ‘There are many conceivable ways of telling a story, some of them known and some still to be discovered.’ Bertolt Brecht

|